Museums present something of a moral dilemma: they seek to preserve and share cultural remains, but sometimes without the consent of those cultures' heirs. Moreover, the motives of a museum's benefactors may be more akin to a Roman Triumph's parading of the spoils of war than a genuine wish to educate and broaden the mind.

There can perhaps be no better example of this than the appropriation of many of the Parthenon's marble statues and friezes by the 7th Earl of Elgin in the years 1801-1812. These have been displayed in the British Museum since 1816, an act that was controversial even then. Once Greece regained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, it began asking the U.K. for the return of its property, an ask that has gone unfulfilled to this day.

I wanted to view the Marbles at the Museum in the hopes that the next time I did so, it would be in Athens after they had finally been returned.

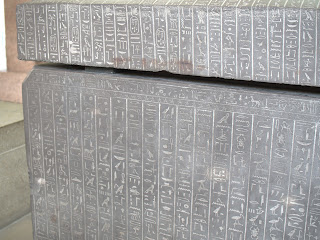

I also wanted very much to see the Egyptian galleries again, though once more I found myself questioning the reasoning behind their being there at all. It is good to preserve culture, to learn from it and appreciate how it influenced who we are today, but is it the right for anyone to step in and decide to do this on behalf of another people, especially against their will or in exchange for money or other more immediate relief that they so desperately need? Egypt's battle with lost cultural heritage is perhaps the most extreme of anyone's. Efforts to curb illegal antiquities export are almost as old as the Western world's interest in ancient Egyptian culture, but so much was still taken, "illegally" or otherwise. So it is with mixed feelings that I see these wonders.

Despite the mob, the heat, and my heart thundering in my chest like a battered piston engine, I took as much care as I could to capture images of every last piece of the Parthenon Marbles. I'm not entirely sure why it mattered so much, but I felt like it was extremely important to have them all documented. There were so many more than I'd thought there'd be; I was shocked by the extent of the theft (for theft is what we must call it, as there is no record that Lord Elgin actually received permission from the Ottoman governor of Greece to take the pieces).

The Rosetta Stone. G was surprised at how small it was. Given its impact to understanding the ancient world, its no wonder that one might envision a monolith a mile high.

The statue of Ramesses II that Giovanni Battista Belzoni moved from the Ramesseum in Thebes to London. A marvelous feat of engineering, but again, a loss to the people of the country whose forebears created it.